Alice Wormald, Small Variations

In the 1950s, Italian artist and designer Bruno Munari produced a series of portable folded cardboard sculptures he titled ‘Scultura da viaggio’ (Travel Sculptures). He envisioned the sculptures being carried by travellers to accompany them on their journeys. The sculptures were flat packed and designed to be unfolded and displayed in the travellers’ accommodations to provide a sense of aesthetic comfort and inspiration in otherwise anonymous spaces. Travellers could look upon them and contemplate the places they had visited while being accompanied by Munari’s forms.

I first encountered Munari’s travel sculptures at a retrospective of his work at Setagaya Art Museum in the suburbs of Tokyo. In the final days of our trip to Japan in late 2018, Tommy and I happened upon a poster for the exhibition, which was titled Bruno Munari: The Man Who Made the Useless Machines. We were both fans of Munari’s influential book Design as Art and so we decided to weave the exhibition into a visit to Yokohama’s Hara Model Railway Museum that we had planned for our last day before returning home.

The model railway museum houses the collection of the late Japanese train enthusiast Nobutaro Hara, who travelled the world to ride on trains and collect models. Highlights of the collection are an exquisite model train that Hara built at the age of thirteen as well as multiple working model railways. Browsing through Hara’s photo archive, we found photos of Connex trains that Hara had taken during a trip to Melbourne in the early 2000s. I remembered myself as a studious but painfully self-conscious teen going to and from school, endlessly rushing, waiting for or travelling on those trains during the time that Hara took these pictures. There was something both unsettling and exciting about suddenly being reminded of something so familiar, but from another time and from such a distant place – like a geographical anachronism.

After the model train museum, we took the bus to Setagaya to visit the Munari retrospective. The exhibition was expansive and included sculptures, paintings, collages, drawings, artist books, children’s books and hanging mobiles among sketches, posters and experiments. My impression was that Munari was someone who truly loved to make things as a way of building purpose into his life, and I experienced the affirmation that comes from recognising some of your own interests and pursuits in the work of an artist whom you admire. By the time we left the museum, it was dark. We walked through the park surrounding the museum, where park lamps illuminated the ginkgo leaves that blanketed the ground, forming big soft yellow circles. Tommy and I had both enjoyed the exhibition so much that we each bought a copy of the catalogue to take home. It was in Japanese and Italian, but even though we couldn’t read it we could look at the pictures and hold onto the memories of Munari’s exhibition and that last day before we returned to our normal lives.

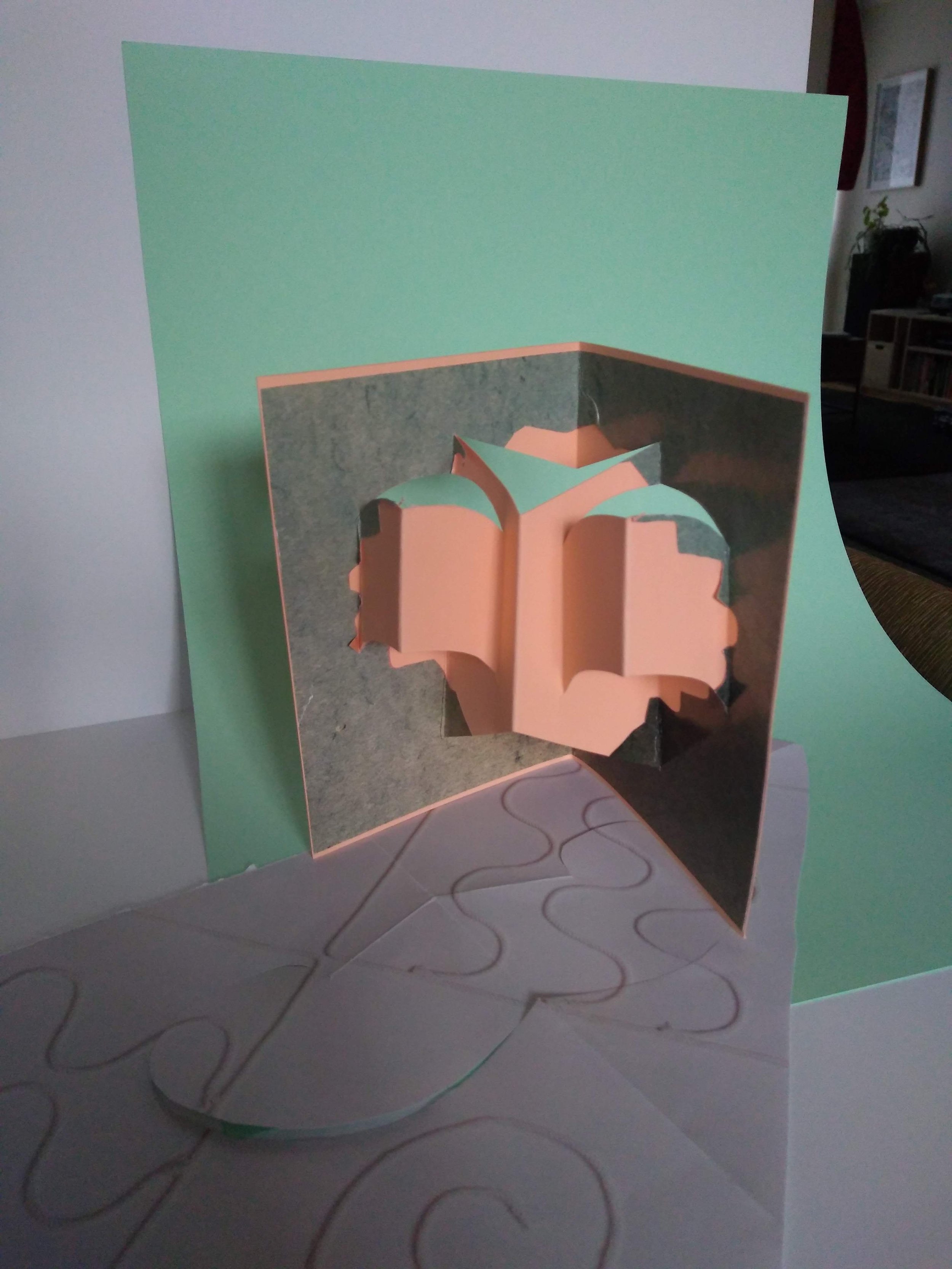

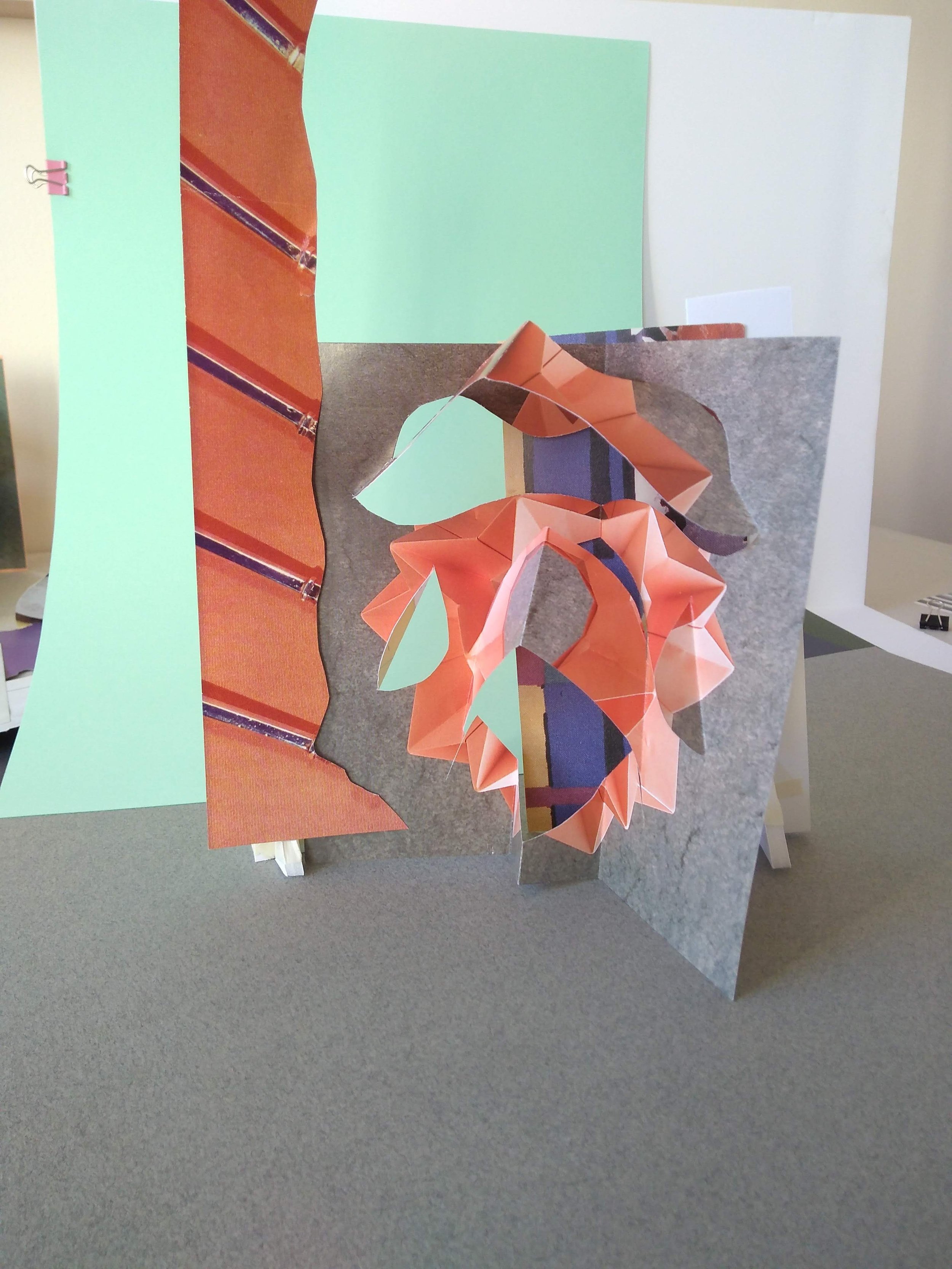

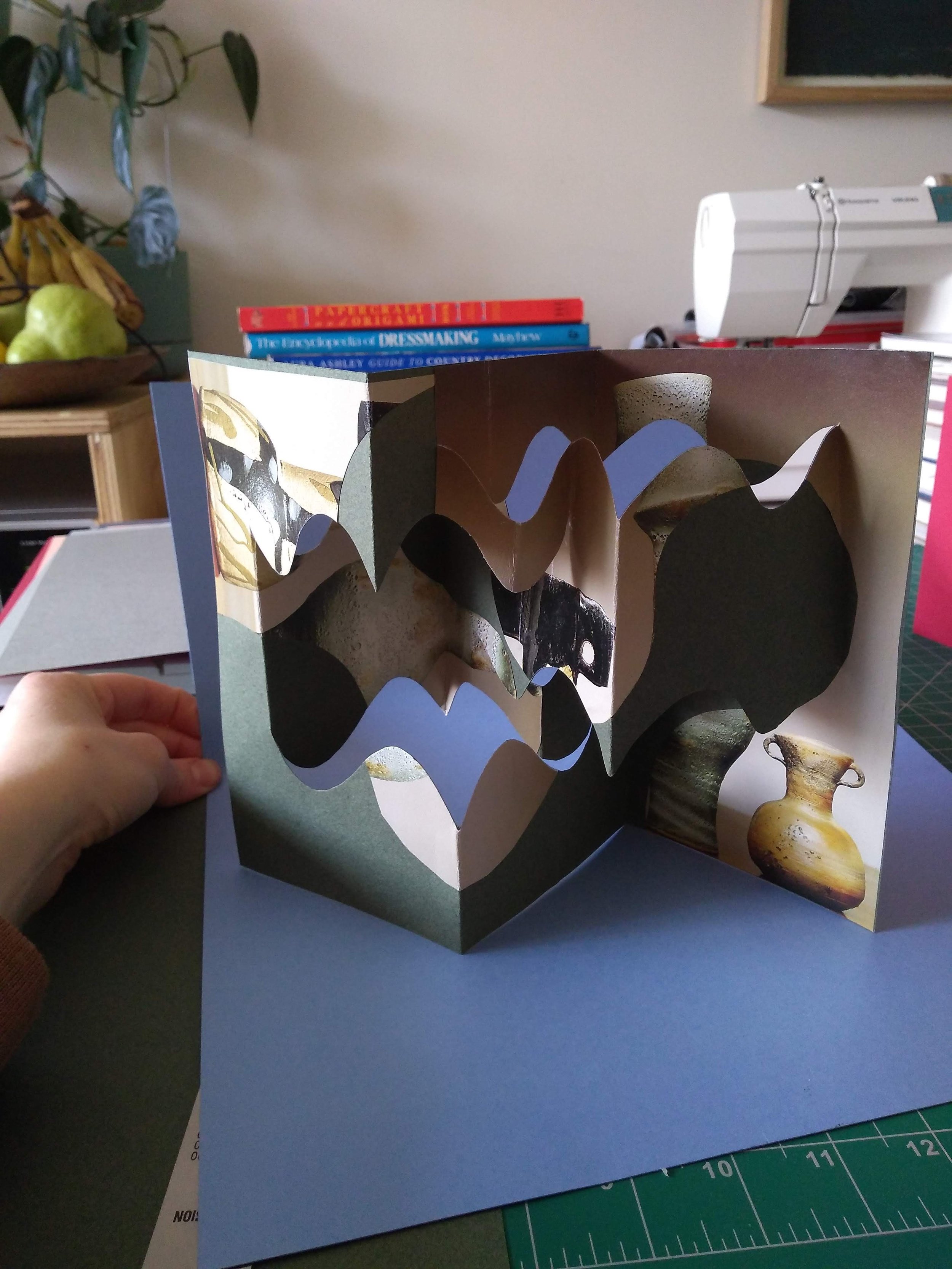

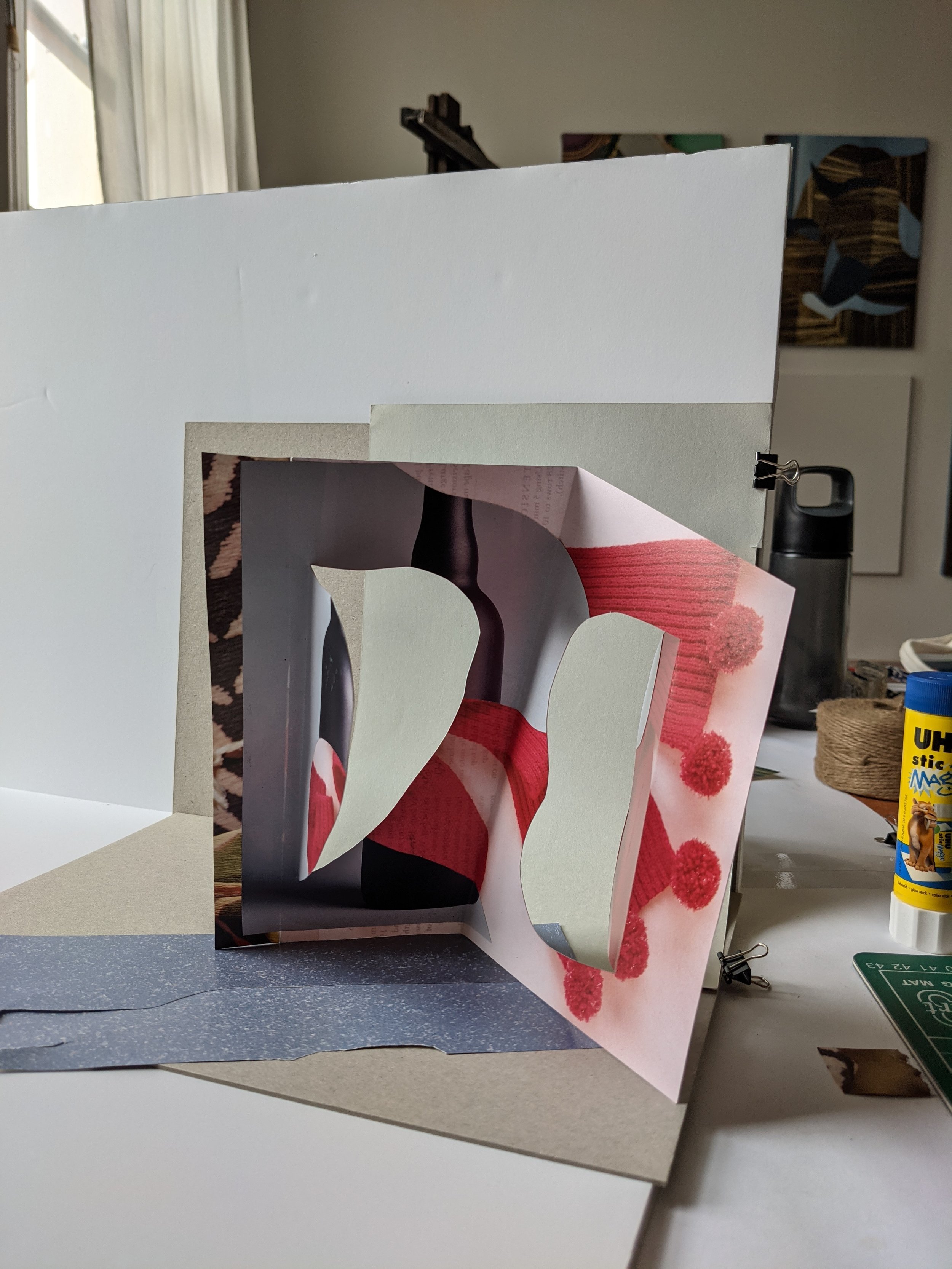

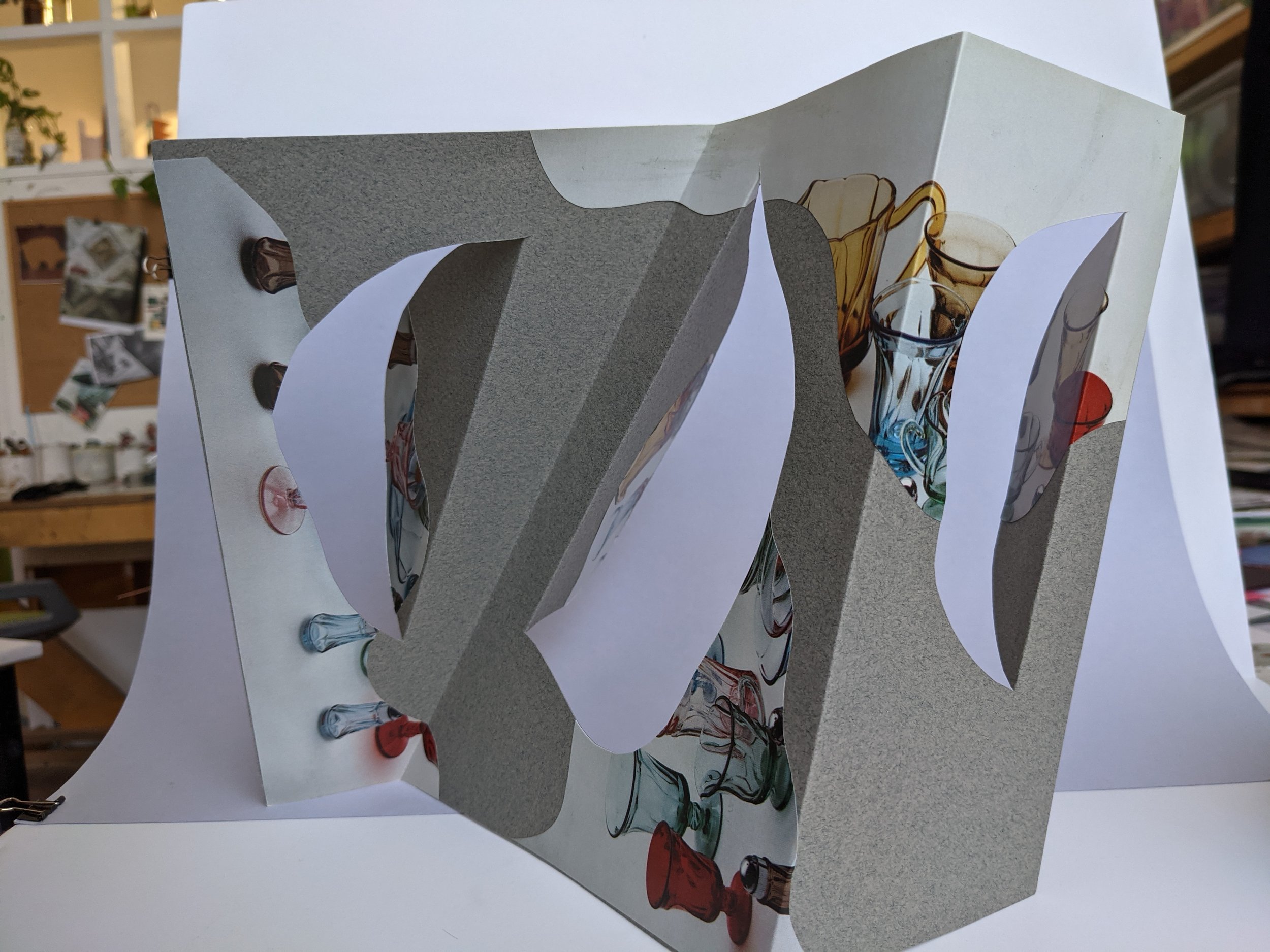

In mid-2020, I was trying to gather some images for collages from the few books I’d collected in the gap between lockdowns. Looking through Tommy’s copy of the Munari catalogue (mine was inaccessible at my studio), the artist’s Travel Sculptures stood out. Their lines, forms and negative spaces reminded me of the intricate instructions for folding, cutting and braiding in the handicraft books I was using for my collages. I started making my own pop-up structures with cardboard and the found images that I had with me at home. My practice became about focusing on a small amount of material that I could work at making work for me, rather than looking outwards and becoming overwhelmed by options and decisions: details, small variations, things that are close at hand.

The work of an artist is often punctuated by periods of expansion and periods of inward focus, and the experiences, thoughts and objects that accompany us during these times. Like one of Munari’s travel sculptures, the catalogue that I bought became embedded with my memories of that day, and offered its own aesthetic comfort and inspiration. It was so valuable to be able to draw on this connection during a period when life, activity and travel were so limited by restrictions and lockdowns. I made my own travel sculptures without leaving my house, and through painting them I wrote my thoughts and experiences into their folds, surfaces and negative spaces.

— Alice Wormald, 2022

Alice Wormald studio views